2 Equality data collection from an intersectional perspective

The Gender Equality Audit and Monitoring tool is an instrument to collect data on (gender) equality in organisations. It is a tool for equality data collection and as such should be embedded in wider reflections on data use for social justice. Critical reflections that approach the purpose of data collection and analysis are currently being developed across diverse fields of application, including ‘data justice’ for developing Artificial Intelligence applications (Leslie et al. 2022), the use of open data and science for Indigenous communities (Carroll et al. 2020), or guidelines for collecting diversity data in universities (Rosenstreich et al. 2022). Although these approaches differ in terms of their field of application and target audience, they agree on a large extend on what equality data collection entails.

2.1 What is equality data?

According to the High Level Group on Non-discrimination, Equality and Diversity of the European Commission, Equality Data is defined as:

“.. any piece of information that is useful for the purposes of describing and analysing the state of equality. The information may be quantitative or qualitative in nature.” (Commission 2021)

Equality data can be collected from diverse data sources, including “population censuses, administrative registers, household and individual surveys, victimisation surveys, attitudinal surveys (self-report surveys), complaints data, discrimination testing, diversity monitoring by employers and service providers, as well as qualitative research strategies such as case studies, in-depth and expert interviews.” (ibid.) The GEAM constitutes one data source among a wider variety of other possible data sources for equality monitoring within organisations. What makes it different is the fact that it includes a carefully selected set of questions to produce both valid and reliable measurement regarding the perceptions of (gender) equality and experiences of discrimination.

Equally important as the data source used, the collection of equality data follows a certain set of core principles (Gyamerah et al. 2022; Baumann, Egenberger, and Supik 2018) described in what follows.

- Purposefulness

-

More data does not automatically imply more justice, as data can also be used for policing and further stigmatisation (Collective 2020). Hence, data needs to be collected with the aim to benefit the involved communities and transform existing inequalities. This in turn implies to explore needs (see next principle: participation!) with minoritised groups before launching a survey. Purposefulness also requires formulating a Theory of Change: to outline the sequence of events and actions expected to lead to a desired outcome. A clear idea on which tested and recommended interventions address existing needs will make data collection and monitoring needs more precise.

- Participation

-

“Nothing about us – without us” (Baumann, Egenberger, and Supik 2018, 108). Stakeholder participation is key for adapting categories, identifying real needs, foreseeing possible risks and preventing data misuse. Co-ownership of data needs to be established at all stages of data collection: during data gathering and analysis, but also when defining its future use, storage and dissemination.

- Self-identification

-

Right to self-determination. Equality data collection involves a critical reflection on the existing/official categories used. Far from being self-evident ascriptions of group membership, socio-demographic categories are “authentic instruments of inequality” (MacKinnon 2013, 1023) as they are woven into political, social and economic processes of exclusion and inclusion. A participatory process with minoritised groups will show how self-descriptions might differ from establish categories and help to prevent further stigmatization. Participants should have the option to disclose or withhold information about their personal characteristics.

- Anonymity

-

Respondents are not linked to the information they provide. Anonymity needs to be distinguished from “privacy” and “confidentiality”. All three concepts aim to protect individuals and their information, they do so in different ways: anonymity makes individuals unidentifiable, privacy gives individuals control over their information, and confidentiality involves protecting information from unauthorized access. These aspects need to be guaranteed before, during and after data collection, for example, by safeguarding how data is stored or by controlling the level of detail published in results.

- Consent

-

Participants need to be informed about the legal framework, data collection purposes, and how data will be processed and protected. It requires explicit affirmation freely given, specific and unambiguous.

- Data disaggregation

-

Data needs to be sufficiently disaggregated using diverse socio-demographic categories such as age, gender, disability/health, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation and others, in order to identify and measure inequalities between these different social groups. A related principle to data disaggregation concerns intersectionality (see next section).

2.2 Equality data & intersectionality

Intersectionality is an approach to understand and transform how socio-demographic characteristics of individuals such as gender, race or ethnicity combine and overlap and are tied to historical and structural relations of discrimination and privilege. The concept of intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to show how Black women encounter combined race and gender (labour) discrimination yet were unable to make legal claims based on this aggravated discrimination (Crenshaw 1990, 1989). Their discrimination case (DeGraffenreid v General Motors) was dismissed by the court, arguing that neither gender-based discrimination (GM did hire white women) nor race-based discrimination (GM did hier Black men) was present. Hence, the combined discrimination between gender and race was rendered invisible, with no legal protection for this “new class of minority” group being available.

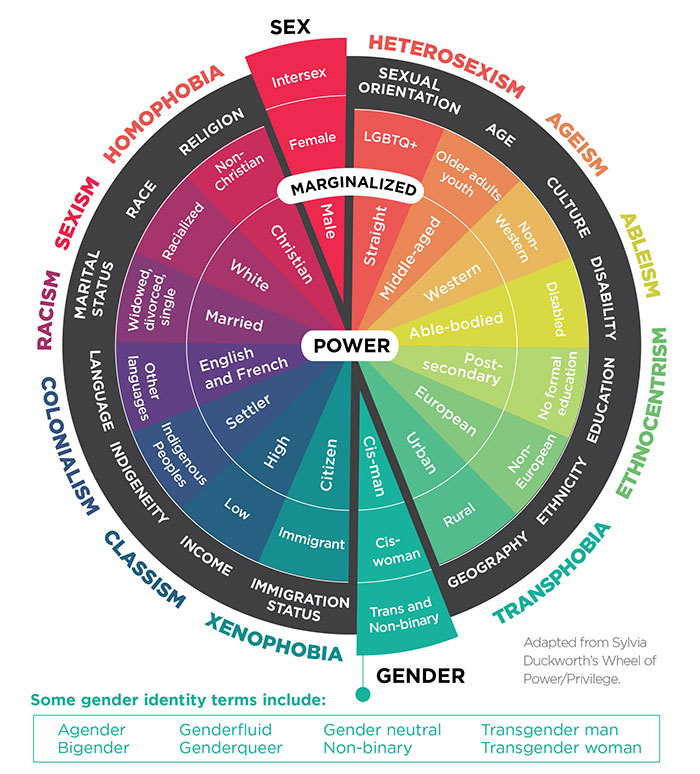

As a critical approach, intersectionality focuses on how power shapes our experience, knowledge and thought not just in relation to gender and race but a whole series of related terms and dimensions of discrimination and privilege. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research has produced a powerful intersectionality wheel that shows various dimensions of social positionality in relation to privilege (at the center) and marginalization (towards the outer ring) and their associated main social processes (e.g. racism, colonialism, classism, etc.).

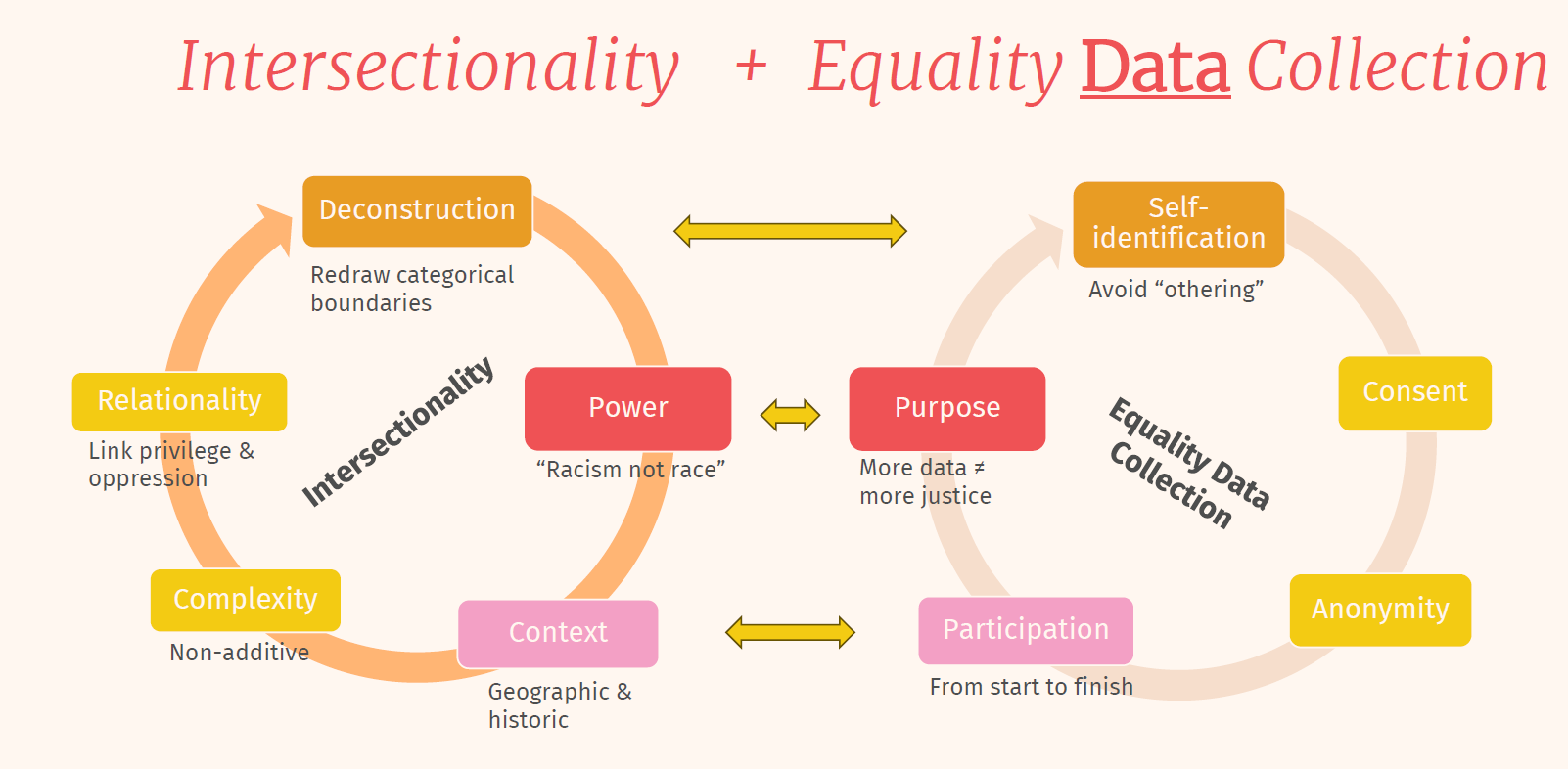

Hence, intersectionality goes beyond the collection and analysis of disaggregated data because it is primarily geared towards the transformation of power relations and thus addressing structural inequalities. To do so, feminist scholars emphasise how social identities and their corresponding categories need to be deconstructed, are always related to other identities, and embedded in a specific social context, that involves historically grown, complex power relations (Collins and Bilge 2020; Misra, Curington, and Green 2021).

Figure Figure 2.1 schematically illustrates how a correspondence can be established between three basic dimensions of intersectionality (Deconstruction, Power, Context) and three principles of equality data collection (Self-identification, Purpose, Participation).

- Power + Purpose

-

Intersectionality is primarily concerned with understanding and transforming the complex power dynamics of social inequality (Collins, 1990; Hunting & Hankivsky, 2020; McCall, 2001). This corresponds closely with the aim and purpose of equality data collection which always is geared towards the benefit of the targeted communities. Data collection needs to have a critical and transformative purpose.

- Deconstruction + Self-identification

-

Social categories are not naturally given, but are in flux and can be deconstructed, redrawn and reconceptualised. Deconstructing categories is thereby not only a discursive move, but also aims at breaking down differences upon which relations of social injustice are organised. This implies a participatory approach before, during and after equality data collection; it also implies that respondents are able to describe their preferred identity in their own terms.

- Context + Participation

-

Context is key for understanding that inequalities are always located at specific sites, composed of spatial, geographic but also temporal and historical contexts. As such, considering context holds the key for deciding on the purpose and priority for data collection. From the perspective of equality data collection, it implies to make use of a participatory approach to detect needs, assess risks, and deconstruct existing categories.

For a more in-depth introduction to the five main dimensions of intersectionality and their relation to equality data collection see Müller and Humbert (2024).

2.3 GEAM & intersectional data

The GEAM does collect different socio-demographic data. By default it includes questions about age, gender, ethnic minority status, sexual orientation, trans history, disability/health, citizenship, country of birth, marital/partnership status, educational level, and socio-economic class.

The GEAM also includes several question modules regarding perceptions and experiences of discrimination, for example regarding bullying, microaggressions and sexual harassment or job satisfaction, and work-family conflict.

Although the GEAM provides a solid basis for collecting data on diverse socio-demographics and possible outcome variables, this in itself is not sufficient for an intersectional approach.

As argued, a participatory approach should be followed from start to finish, involving engagement with the wider (organisational) communities and the diverse stakeholders. Exploratory qualitative interviews should be used at this initial stage to understand needs but also possible risks of data collection and to adapt categories and questions to the local context.

Once data collection has been completed, several advanced statistical approaches are available to take full advantage of an intersectional perspective. Intersectionality is non-additive, meaning that it captures the lived experiences of individuals which always already belong to several socio-demographic categories. Adequate analytical approaches such as Multilevel modelling (Evans et al. 2018; Merlo 2018), latent class analysis (Bauer et al. 2022) or Qualitative Comparative Analysis (Ragin and Fiss 2024) are necessary to capture how individual experiences involve multiple, intertwined social identities inhabiting a variety of positions of privilege and disadvantage.